This one is fairly long, but I think it’s worth the read. I hope so. Anyway, it’s the Christmas break – you’ve got time to kill…

When it comes to performance, it’s easy to believe you’ve either got it or you haven’t. Luckily the reality is a lot murkier, in your favour.

True, some people have latent ability or learn rapidly, but often the best of the best have created advantages for themselves- or had them created by others- that you can have too.

Going beyond talent

This concept is well-covered in Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers (highly recommended). It explains how top performers got that way, talent be damned.

In many cases, some inherent advantage shows up in these peoples’ lives which is then built upon.

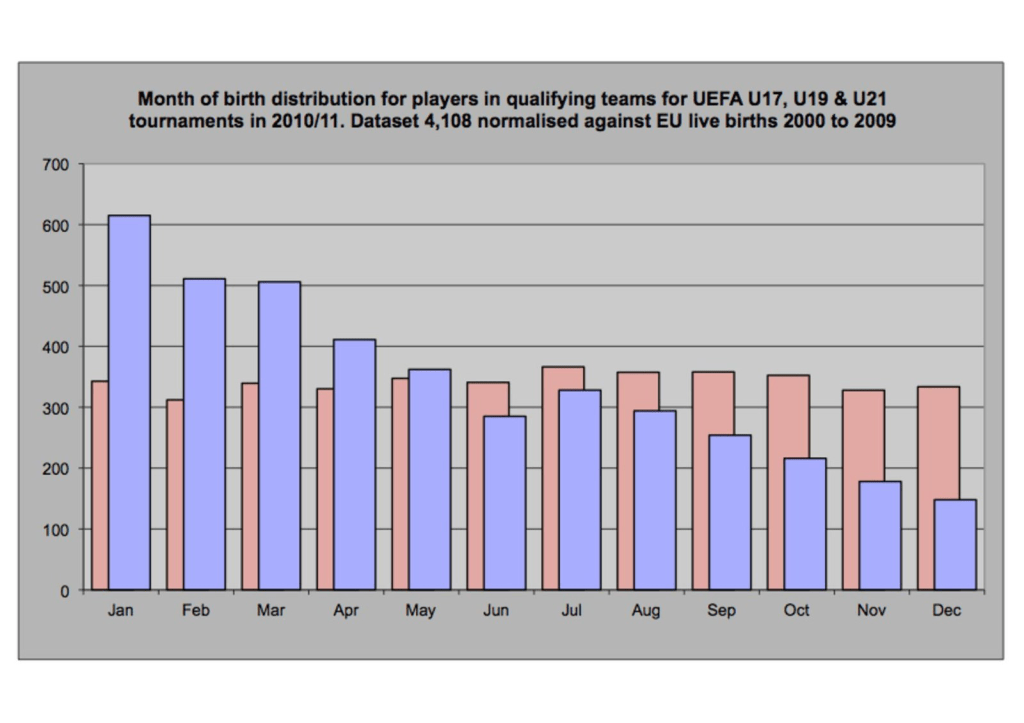

Take elite athletes: top players are commonly born toward the start of their sport’s respective age bracket. This is a small detail, but think about it: if you’re on the fringe of your age bracket you’ll be on average 6 months older than your teammates, and 11 months in some cases. For a child, that’s a leap in physical and mental development. This translates into higher ability at the same “age”.

Coaches prioritise their star players, so these ‘older’ players consistently get more attention and game time. They can more actively train their minds to read games and strategise, because they aren’t physically flat-out during play. By adulthood, they’ve had thousands of hours more useful practice than some of their peers who might be more talented.

The same player born mid-year might have been totally average; an early birthday turns into a lifelong performance advantage. A real world example of hard work beating talent, just with a few extra factors at play.

Obviously you can’t change when you’re born, so not very actionable. “Wanna succeed? Change your birthday!” We need to think a bit smaller.

Don’t let the basics take too much effort

Clearly then, your environment can position you for greater success. Better still, in less-rigid cases than an age bracket, you can optimise your existing environment with small improvements. Japanese business culture calls it Kaizen and it gave companies like Toyota and Nissan an edge when they arrived in the West.

Consider another Eastern cultures, in the stereotype that being Chinese naturally comes with higher mathematics ability.

Obviously I’m not endorsing those kinds of generalisations.

But in terms of attainment by Chinese students (and other Asian countries), the average is really often higher. Something about the way maths is taught or examined makes a positive difference.

It’s actually because of their language; the way they write their numbers. There’s a simplicity to it which has a knock-on effect.

I can’t speak Chinese, so I’ll highlight some European approaches then contrast them to make my point:

- In English we have numbers like sixteen and sixty, which sound very similar. The teens break the pattern of larger numbers ending in the unit number (as in fifteen Vs twenty-five; there’s no ten-five).

- French has loads of examples, but my favourite is 99. It’s spoken as quatre-vingts-dix-neuf, which means “four twenties ten nine”. Not joking.

- In German, the number 28 is achtundzwanzig, which means “eight and twenty”. All numbers between 21 and 99 give their digits in a funny order like this.

By contrast, in many Asian languages numbers are brutally simple. 15 is essentially “ten five”. 99 would be “nine-tens nine”.

Compare the difference when adding 65 and 32:

English: 65 + 32 = sixty-five + thirty-two (as spoken) = six tens and five ones + three tens and two ones = nine tens and seven ones = ninety-seven = 97.

That’s a lot of conversions, and this is happening whether you know it or not. It’s part of why so many people struggle with mental maths.

Chinese: 65 + 32 = [six-tens] {five} + [three-tens] {two} = [six-plus-three tens] and {five-plus-two} = [nine-tens] and {seven}. Done. By the time you’ve done the addition, you’ve already got the number with no further conversion.

Because there are less steps, larger numbers aren’t much harder to handle.

Relate that back to our example about athletes: having an edge in the basics (higher age/simpler numbers) lets you focus more on the more difficult stuff (game strategy/complex arithmetic and algebra). That initial edge enables better practice and higher average ability.

Your native language is about as easy to change as your birthday, so this is impractical to copy too.

What you can do is apply the same principles to more controllable areas.

Tiny improvements stack up across years

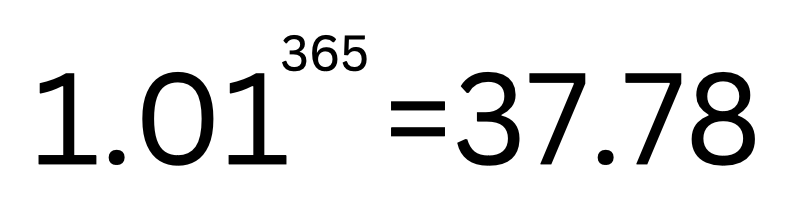

By making a task one per cent easier, you don’t just go one per cent faster. You also think less about the basics and have more mental bandwidth for the difficult parts. Over weeks, months and years, the differences compound and put you in a different league. Even small changes to minor skills accumulate over time.

Not a realistic prospect, but food for thought. Small changes count!

When I first got into computers as a kid, I loved the idea of keyboard shortcuts. If there was a way to do something without the mouse, that was interesting to me and I wanted to know what it was. I learned tons over the years.

The payoff came 8 years later, writing my dissertation for my Master’s degree. My full-time job relegated writing to evenings and weekends, making time precious. By now I could move through a word document, highlight text, delete whole words or lines of text, jump between programs and resize windows all from the the keyboard.

Each time I went without the mouse or touchpad, I only saved seconds. Over the hundreds of hours I spent writing they’ll have added up to a few hours; enough to save an evening or two. In hindsight those are evenings I really needed to save. Not to mention the momentum it let me build up from physically and mentally focusing on doing one thing at length. Given how narrowly I made the grade, this was the difference between me receiving the top classification or falling short.

“What if I’m not writing a dissertation?”

It’s easy to roll your eyes at the examples given. You can’t change your birthday or your native language, so what’s the point? That’s true; you can’t often manufacture a change so extreme. You also don’t need to. These tiny changes stack up over time so any small tweak can transform your results.

Here are some things I’ve been able to do which enhanced my day-to-day:

- I’ve got a laptop charger at home and work. The time not spent crawling under desks to unplug it or making sure it’s packed before leaving the house isn’t much, but it streamlines my whole routine. It saves absolutely no time during the workday, but I get up to speed in the morning more consistently.

- Everything we need for our morning coffees is laid out the night before, right down to having the right amount of water in the kettle.Again, this doesn’t buy us any extra sleep but it makes the half-awake start of the day that bit smoother and less fuck-up-able.

- My whole morning routine is laid out in an app on my phone. However dazed I am, I can just do what’s on the screen and press ‘done’ for the next one to appear.

- I’ve registered multiple fingers on each hand in my phone’s fingerprint scanner. I never have to shuffle my phone between hands or pick it up to unlock it.Less shuffling around is less potential for a drop too, which saves me from those sickening “is it broken” moments when it lands face down.

- My bag has a little pocket that’s just for my bus ticket. Not having to dig through my pockets and wallet makes for a less tense commute.

- Using a password manager means I rarely type a password and almost never have to recover one. One of my best investments of the 2022.

- Everything at home is stored as close as possible to where I’ll be when I need it. This is as much about momentum as it is convenience. I don’t have to walk away from what I’m doing and risk getting distracted.

None of these steps are exactly groundbreaking, and that’s the whole point. They don’t have to be.

Mirroring my last post on motivation vs discipline, sustainable habits and routines should start small. That doesn’t mean you have to settle for small results over time.

If you can understand the change you want to make and break it into bite-sized changes like this, you’re much more likely to succeed.

Start looking out for little snags in your day that bog down your momentum. You’re bound to find some and fixing them is really satisfying.

Your ideal day probably pans out close to your current one, but you’ll get much more out of it. Give it all a try!

Leave a comment